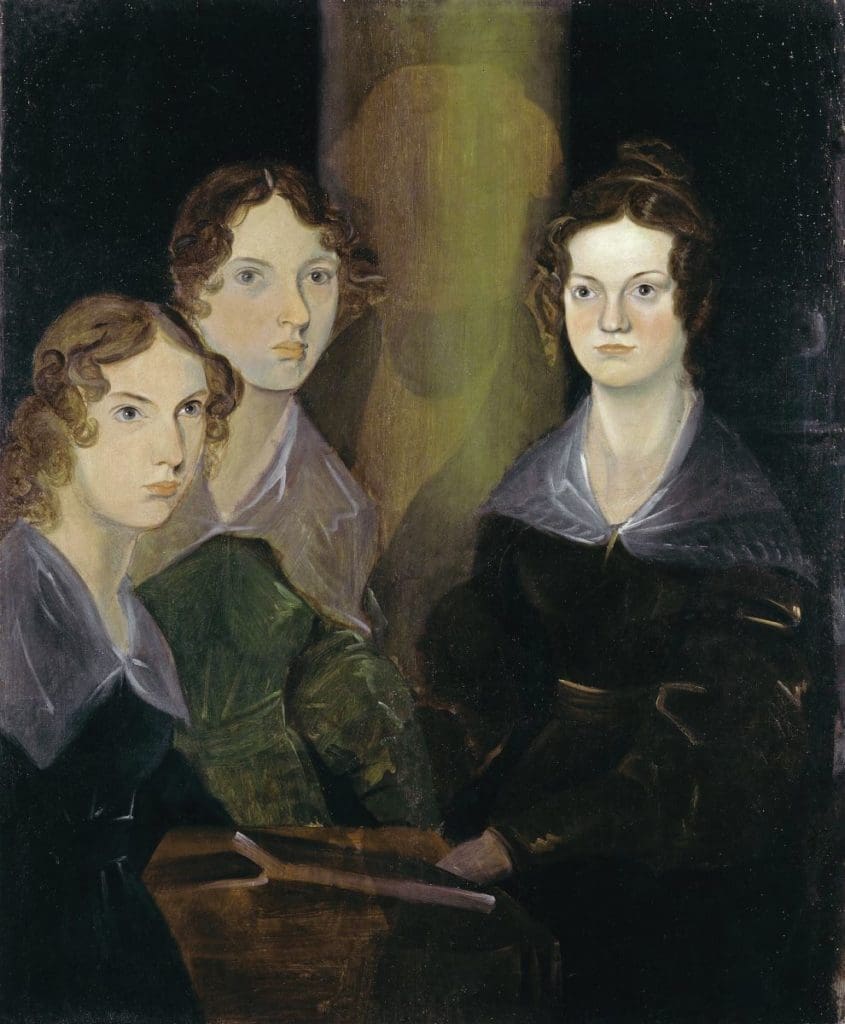

Bob Gwynne, associate curator at the National Railway Museum, describes how the lives of the famous literary family the Brontës was intertwined with the pioneering days of the railway network, with their journeys providing a touchstone of what rail travel was like in those early days.

On August 24, 1847 a package was dispatched from Keighley station, which had opened in March of that year, to a publisher in London. Handwritten and running to around 400 pages the resultant book, ‘Jane Eyre’ (first published in October 1847) was an instant bestseller. The book brought the writings of a singular family living on the edge of the Pennine moors to the attention of literary Britain. We are, of course, talking about the Brontës – a family of literary sisters and poet brother, who have been of interest to many ever since that precious parcel made it into print.

Charlotte Brontë had first travelled by train as early as 1837 with her friend Ellen Nussey on a trip to Bridlington. The journey was on the Leeds and Selby, one of the first lines in Yorkshire and the first line in the world where the trains were hauled through a tunnel by a steam locomotive.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

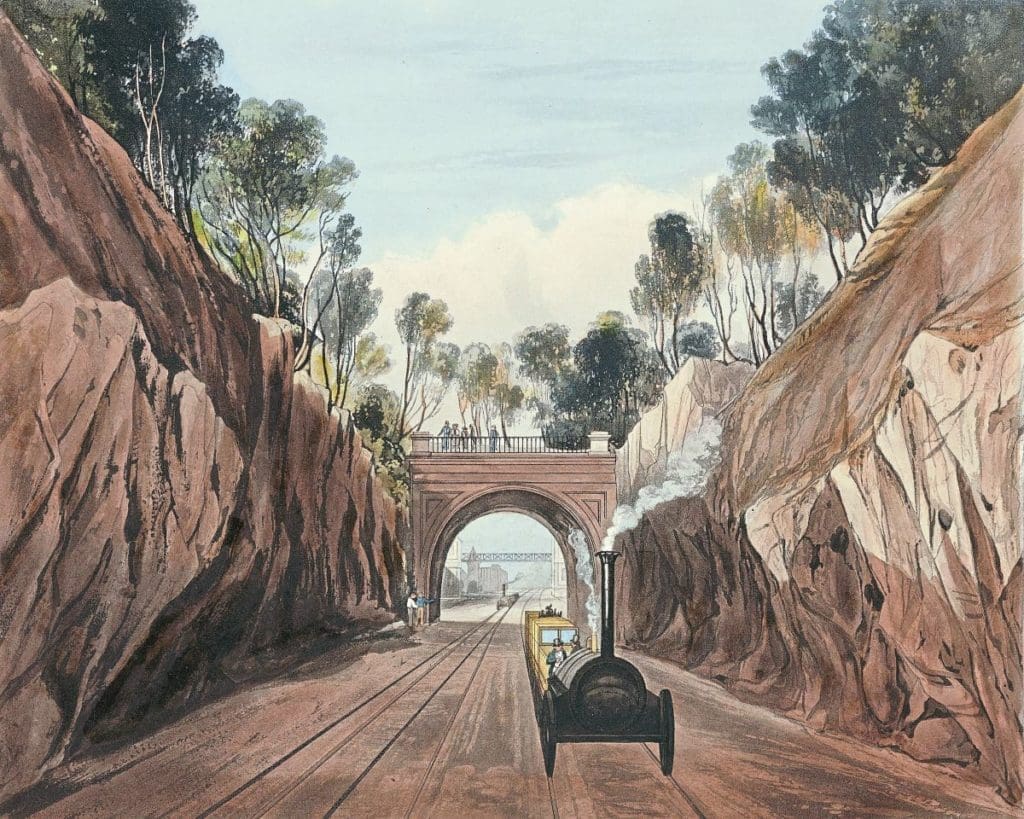

The Leeds station was at Marsh Lane and travellers would have entered Richmond Hill tunnel almost as soon as the train was underway. The tunnel had whitewashed walls with copper sheets at the entrances and ventilation shafts to reflect light into it – presumably to reassure passengers in what was then a unique experience. Those in Third Class carriages travelled in vehicles with no roof, and First Class was like a road coach with luggage going on the roof. Richmond Hill tunnel is no longer there, having been opened out in the widening of the approaches to Leeds when the direct line to the ‘new station’ was built in 1893, but the site of Marsh Lane station remains as a siding on the north side of the mainline when approaching Leeds from the east.

The Leeds and Selby carried 261,639 passengers the year after Charlotte travelled, its marketing as the route to Hull clearly being a success. The station at Selby was next to a road bridge across the Ouse and alongside the quay for the ferry to Hull. This station is still there, next to today’s, having been used for many years for goods. It is one of the world’s oldest complete railway termini. Given that the Leeds and Selby ran a connecting coach from Bradford, and a connecting ferry from Hull, the line was actually a pioneer of transport integration long before many places even had a railway.

Charlotte’s journals occasionally mentioned the costs of journeys, but never the (dis)comfort or difficulties encountered. Yet these were the days when the stations had no platforms, trains no continuous brakes, and track was often set on stone sleepers. If you had the money, and wanted that to be known, you might travel in a ‘coupe’ – which was a First Class carriage with side and front facing windows, like a Hansom cab. With no continuous braking system, starts and stops could be very rough indeed, and stories of people being thrown through the front windows in these carriages are not unknown from these early days. But like passengers of today, Charlotte clearly took the workings of the railway for granted, or at least with a degree of sang-froid. The newspapers highlighted the dangers and incidents, not the day to day.

Not long after the trip to Bridlington, Charlotte’s sisters Emily and Anne travelled to York to see the sights, joining a growing throng that were beginning to make the working town (with a collection of historic buildings) into a tourist attraction. Again, their journey was likely to have been by road coach to Leeds (Marsh Lane) and then on to York by rail, where the original station was at this time outside the city walls; the magnificent new station by local architect GT Andrews inside the city walls did not open until January 1841.

Railway employee

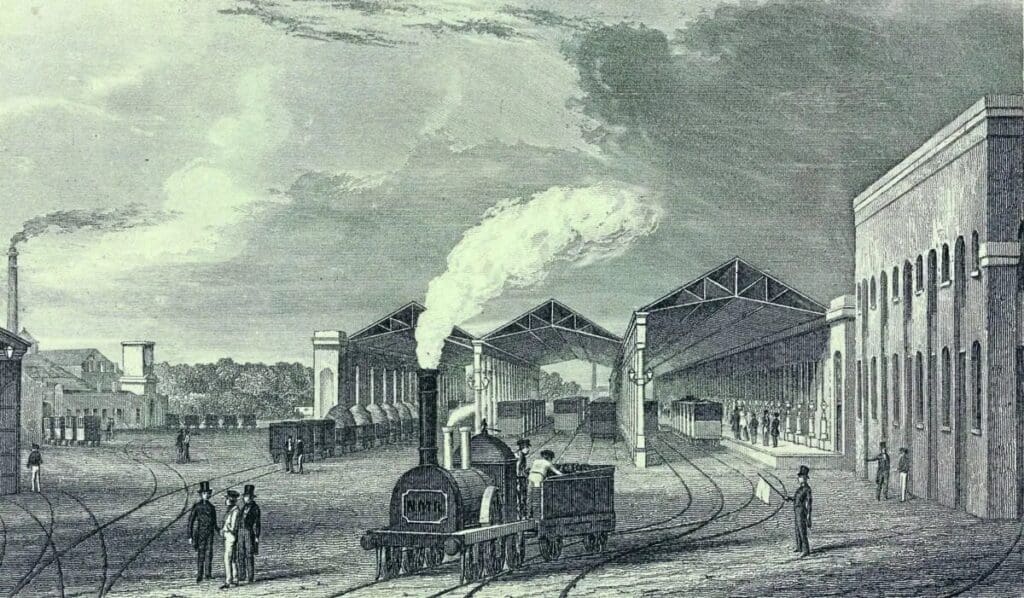

Meanwhile their brother Branwell, often written up as a sort of doomed, feckless poet type, is likely to have already travelled on the Liverpool and Manchester railway in 1837. He was clearly an impressive, well-educated young man at this point in his short life because, in 1842, he landed a job on the Manchester and Leeds railway as the assistant clerk in charge at Sowerby Bridge station.

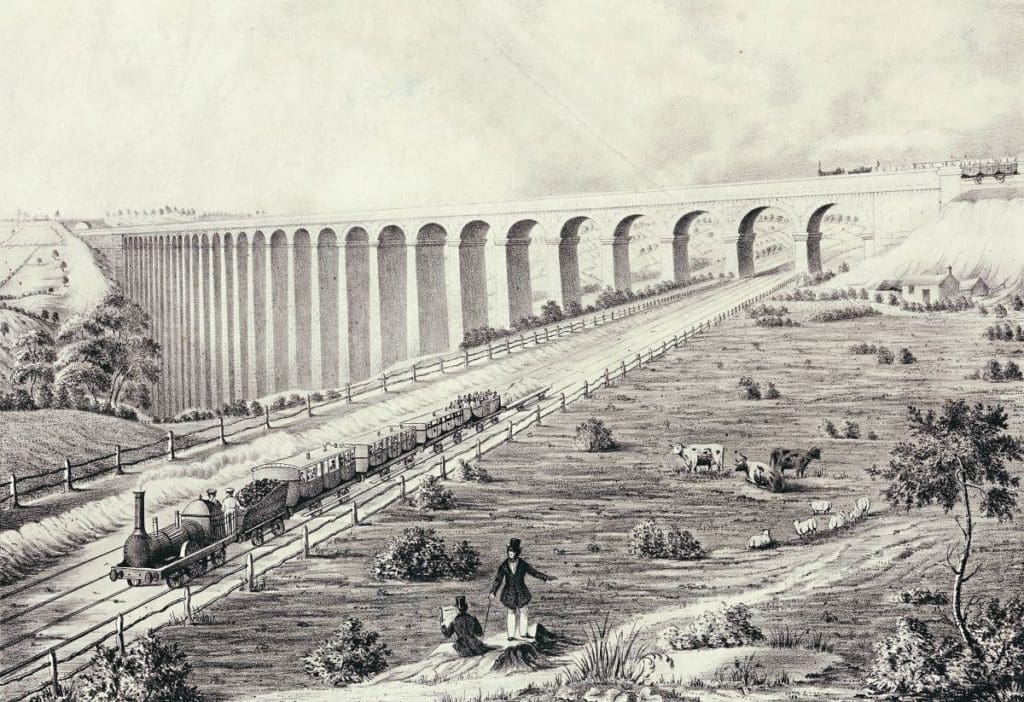

This railway was one of those colossal achievements that we now take for granted: 116 bridges and eight tunnels, all built by hand, and with Summit Tunnel the longest tunnel on the planet when it opened.

This is how the local newspaper reported the first train arriving at Branwell’s place of work: “There being no room in the carriages, the adventurous travellers mounted the tops of the carriages, where already as many persons were sitting as could be accommodated in that position; but those who could not sit stood upright, until the whole of the carriages were covered with a crowd of standers, and in that fearful position did they remain all the way to Hebden Bridge, stooping down as they passed under the tunnel and the numerous bridges on the line, and then rising and cheering like a crew of sailors to the astonished spectators!”

Branwell does not comment, however, and quite what George Stephenson made of all this (he was also there) is an interesting question.

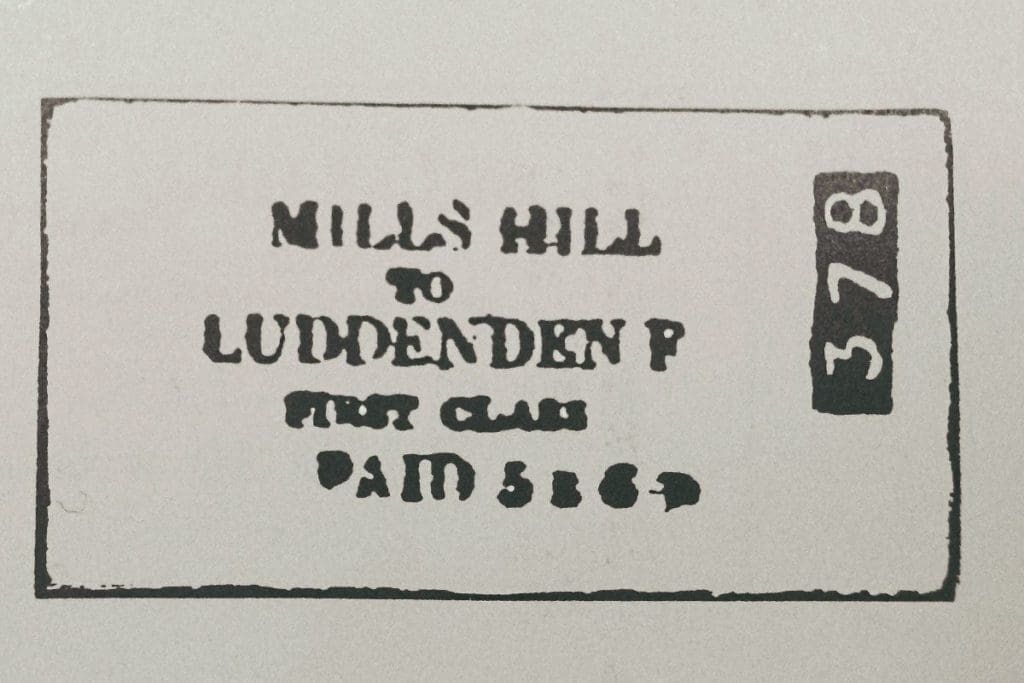

Branwell did well enough at Sowerby Bridge to be promoted to ‘Clerk in Charge’ at Luddendenfoot station on an enhanced salary. There his diligence certainly won him friends from the local businesspeople, even if it did not extend to keeping a close eye on the takings. Doodling in the margins of the station’s ledgers was one thing, but not giving correct returns was another.

The M&L was the second railway to run with the Edmondson ticket system. The journal Herepath reported on August 24, 1839 that “Mr Edmondson’s system of issuing tickets has fully met the pressure of business. On Monday, 1519 passengers were booked at the Rochdale station with equal ease and despatch”.

The system meant that ticket sales could be easily audited, and the M&L had a zero-tolerance approach to misdemeanours. Branwell was dismissed when a discrepancy in the accounts came to light, though research suggests that this was not his fault. Local merchants and mill owners petitioned the company for him to be retained, but it was not to be.

For a while, another railway position seemed possible when the Manchester, Hebden Bridge and Keighley Junction Railway was promoted, with Branwell’s father being one of the backers. However, the promotion of this railway came just before the collapse of the railway boom in 1846, so Branwell’s ambitions in this area were not to be realised, leaving him to try his hand at tutoring and a career in literature.

During his railway years, he had acquired a friend in railway engineer Francis Grundy. Grundy would go on to assist with the development of lines such as that from Skipton to Colne, but when he first met Branwell he was sharing his lodgings with George Stephenson’s nephew George Robert Stephenson (1819-1905), assistant engineer on the M&L.

To London and abroad

As part of their rather high class education, Charlotte and Emily were whisked off to learn French in Brussels in February 1842, travelling with their father by train from Leeds (Hunslet Lane) to London – a journey of a mere 10¼ hours (if they took the mail) for £5-2s First Class (equivalent to more than £600 in today’s money using the Bank of England inflation calculator).

‘Time is allowed at Normanton and Derby for refreshment’ stated the timetable of the day; the Midland Hotel at Derby is still there, though the Railway Hotel at Normanton has long since been demolished. At London, a packet boat took them from near London Bridge to Ostend, and then by horse drawn carriage to Brussels.

The Brontës’ journey was no doubt helped by the fact that the independent railways of this newly connected system had agreed to co-operate on a range of things, from ticketing to what would now be called ‘group standards’ (for buffer heights etc) via the Railway Clearing House, which started its unifying work on January 2, 1842. The sisters’ route to London was by the North Midland, Midland Counties and London and Birmingham via through carriages; Leeds did not get a through train until 1846. It would also have included a descent of the cable-worked Camden bank into London (Euston); the L&B engine would have been detached and gone to the engine shed at Camden, which is now the ‘Roundhouse’ arts venue.

When their aunt Branwell died (she had been a surrogate mother to them), Charlotte and Emily returned home, although Charlotte repeated the journey to Brussels on her own the following year.

Growing tourism

Meanwhile Anne and her brother Branwell were at Thorp Green Hall, about halfway between York and Knaresborough and not far from Hammerton station. Things did not go well, and both returned to Haworth by July 1845. Branwell was by all accounts somewhat lovelorn, having had an affair with his employer’s wife whilst there.

Did Branwell attend the opening of the York and North Midland line to Scarborough on July 7, 1845? This would have been a grand occasion and he had worked for the railways, and was still hankering after another post, so it is possible. The reports of this event are typical for line openings of the time, and usually anyone who could went along: “After a ‘public breakfast’ in York, the train of 35 coaches headed for Scarborough. Free beer was provided when the train stopped at Castle Howard by the Earl of Carlisle”.

The train would have left from the GT Andrews-designed station inside York’s city walls, which had opened by then. The station was built inside the city walls (against George Stephenson’s advice and giving an operating headache to those trying to work trains to anywhere north) at the insistence of that bombastic chancer, and three times mayor of the city, George Hudson. Today it is now the headquarters of York City Council, with the boardroom of the York and North Midland a meeting room, while part of the station’s platform canopies have been re-erected as a rather grand cycle rack. It is a curiously fitting reuse for a building that was, in its day, a large symbol of modernity.

Being back home clearly did not suit the restless Branwell, who was soon off on a trip to Liverpool with his father’s sexton. Their journey would have started on the turnpike to Hebden Bridge station, then on the Manchester and Leeds railway, followed by Liverpool and Manchester.

In Liverpool, they would have arrived at Lime Street station, which had only opened in 1836 and which was reached by a gravity trip from Edge Hill (with cable working in the other direction, as at Euston) – though, as usual, our passengers (if they did arrive in the city this way, and it is most likely) made no comment. The trip to Liverpool clearly did not help that much, as Branwell soon after sank into alcoholism and very likely drug dependency via laudanum, a dilute form of opium.

Boom and bust

Aunt Branwell had left Branwell nothing in her will, despite him being a favourite and indeed bearing her name. In Victorian England, it was single women who needed a dowry, not men of working age, so Anne, Emily and Charlotte each got £900 of investments, shared between the lead mines of Swaledale and the York and North Midland Railway. In April 1845, Charlotte wrote: “Emily has made herself mistress of the necessary degree of knowledge for conducting the matter, by dint of carefully reading every paragraph and every advertisement in the newspapers that related to rail-roads and, as we have abstained from all gambling, all mere speculative buying-in and selling-out, we have got on very decently.” Decently and thankful enough for all three sisters to contribute £1 to the George Hudson testimonial fund (as listed in the Railway Times September 27, 1845).

When the bubble finally burst in 1846, it was Charlotte’s publisher George Smith who ensured she avoided the worst problems of the crash. Writing to her old friend and former teacher Mrs Wooler, she wrote: “The business is certainly very bad – worse than I thought, and much worse than my father has any idea of. In fact, the little railway property I possessed… scarcely any portion of it can with security be calculated on. When I look at my own case and compare it with that of thousands besides – I scarcely see room for a murmur. Many – very many are – by the late strange Railway System deprived almost of their daily bread.”

Charlotte’s novel ‘Jane Eyre’ became a bestseller in 1847, which must have helped her to be sanguine about a situation that ruined many, including people near Haworth that she knew. Charlotte is thought to have acquired the unusual surname ‘Eyre’ on a visit to Hathersage (by train and coach) to visit her friend Ellen Nussey in 1845. There are memorials to the Eyre family in the church at Hathersage, and she was there to help her friend prepare a house for her brother the Reverend Nussey, recently married after Charlotte had turned him down.

At the time, Charlotte could have consulted a Bradshaw to work out the journey, by now a common occurrence as the publication had been in print since May 1839. Anyone consulting their Bradshaw was of course presented with a range of hotel and other advertisements on each page, the ‘pop-up’ ads of their day, including some names that are still familiar – Schweppes, Heals (the store), Robinson’s barley water, and Crosse and Blackwell chutney.

In July 1848, Charlotte was off to London again, this time with her sister Anne, and this time able to take a train directly from Keighley, the station there having opened the year before. From Leeds it was the night train, arriving in London at 08.00, giving them plenty of time to surprise their publisher with the news that his new (and lucrative) authors were not men but young women.

The whole trip cost them the equivalent of three-quarters of their annual salary when they were governesses, proving that whilst travel over relatively long distances was now relatively easy, and acceptable for unaccompanied women, it was by no means cheap. Charlotte noted in her cash book the cost of a Second Class Keighley to Leeds and First Class Leeds to London ticket for both of them one way was the equivalent in value today of over £500.

Final journeys

Sadly, whilst the family was now beginning to get somewhere with their literary ambitions, Branwell Brontë died in September 1848 and was followed in December by Emily, both of tuberculosis. Given the mortality rate of where they were living at the time, and Branwell’s addictions, his death cannot have come as a great surprise. But Emily’s death would have been a shock, and it was followed in 1849 by the diagnosis that Anne also had the same killer disease.

Anne had time for one last trip to York, taking the 1.30pm train Keighley to Leeds on May 23, then on to York and staying overnight in the George Hotel on Coney Street (the site is now, appropriately enough, partly a bookstore). They had time for a visit to York Minster, and then on to Scarborough where she died four days later. The sad details of Anne’s final journey nonetheless do show how, in little more than a decade, trains had become a normal means to travel.

Anne’s death left Charlotte and her father to deal with the fame of the family, which was now a potent mix of literary power and sympathy for the loss of such powerful writers at such a young age. Charlotte soon found herself invited places, the first major trip being to see a significant fan – the education and anti-poverty campaigner Sir James Kaye Shuttleworth at Gawsworth Hall in Burnley. The route there would have been along the Skipton-Colne line that had been worked on by her brother’s friend Francis Grundy.

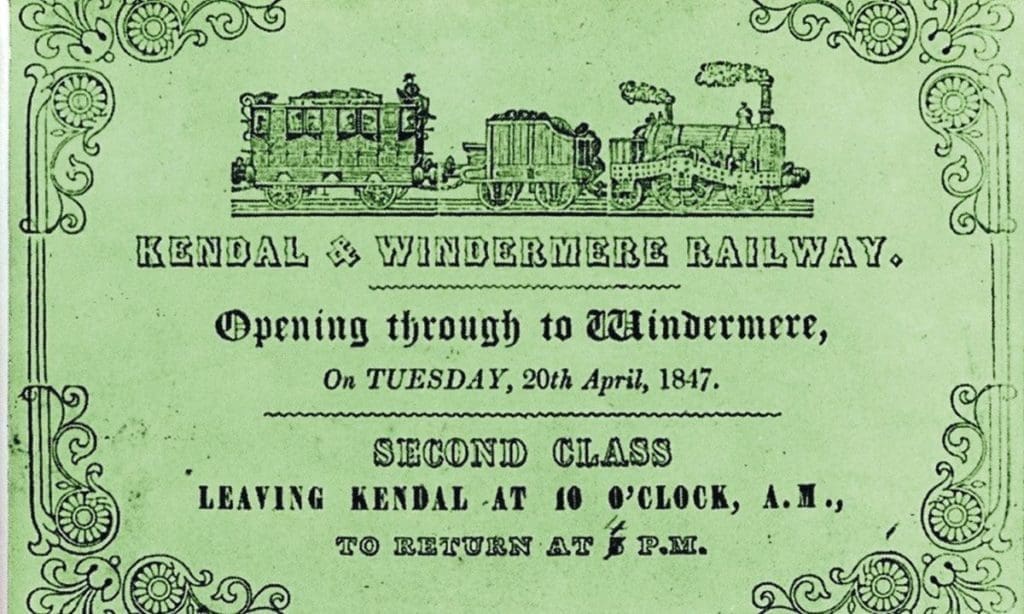

In 1850, she would stay with the Shuttleworths at their holiday home on Windermere, where she met fellow authoress Elizabeth Gaskell, who would become her biographer. In July of the same year, she travelled up to Edinburgh to meet her publisher and his family. The journey would take her over the Royal Border Bridge approaching Berwick, which had opened in March of that year. But, of course, about this she did not comment.

The following year she was one of the six million visitors who went to see the Great Exhibition in London, visitors whose journeys were enabled by the fact there were now 7000 miles of railway linked to London, and lots of people prepared to sell cheap excursions to the capital. Charlotte would visit the exhibition five times, slotting the journeys to London in amongst others to Hornsey, Manchester, Kirkcudbright and Ilkley – all pretty much without comment, apart from the time she lost some of her luggage when changing trains. It seems a very modern attitude to transport, similar to how most people travel by train today: no comment unless something goes wrong.

In June 1854, Charlotte married A B Nicholls, who had been her father’s curate and who was from Ireland, just like her father (whose accent she reportedly had). The honeymoon would start in Conway (Conwy) and then on via Holyhead to Ireland. From Kingstown (now Dun Laoghaire) into Dublin, it would have been by the standard gauge railway that had opened in 1834 and which would not go over to the Irish ‘standard’ gauge of 5ft 3in until later.

Arrival would have been at Dublin Westland Row station, now Dublin Pearse, and from there across the city to Dublin (Broadstone) for the railway built by the Midland and Great Western Railway, which by 1851 had opened to Galway. From Athlone on the M&GWR, the easiest route was a boat down the Shannon navigation to Nicholls’ family home at Banagher.

Rails to Haworth

Charlotte would die not long after this memorable trip in March 1855 aged just 38, the most likely cause being acute morning sickness. Then, as now, there is nothing quite like an early death to promote sales; the Brontës were by then literary superstars and the ‘pilgrimage to Haworth’ soon got underway.

In 1861, engineer John McLandsborough was visiting Haworth and, after discovering there was not yet a railway, he suggested there should be. Within a month of its opening in April 1867, the Keighley News reported: “It has been the means already of bringing thousands of visitors to the ancient village of Haworth. During the past few Sundays, hundreds have been enjoying the pure air and mountain breezes in the romantic neighbourhood. To all appearances it is very likely to become a general pleasure locality in the summer months.”

This line is still with us today thanks to the Keighley and Worth Valley Railway Preservation Society, who refused to accept the changes that swept through Britain in the 1960s, and who reopened the line after it was closed by the state. As a result, Haworth station is maintained in a way that McLandsborough would recognise, and literary pilgrims can still make their way by train to visit Haworth Parsonage where this famous literary family once lived.