Still reeling as the implementation of Dr Beeching’s Reshaping the Railways programme of station and line closures pressed ahead, the railway experienced a bad year in 1967. In the first of a series marking the 50th anniversary of 1967 railway accidents Fraser Pithie considers a fatal collision on the West Coast Main Line at Stechford in the West Midlands.

ASSUME NOTHING, the mantra pressed home time and time again across safety critical industries and services. Indeed, it can be extended across most things in our daily working and personal lives.

Nevertheless history has shown on numerous occasions the relevance of the old saying that ‘familiarity breeds contempt’. Despite complex and well-designed signalling and interlocking systems, the railway is not excluded from the consequences of assumption, not least because signals and instructions require interpretation, observance, communication, and crucially, application by individuals.

By February 1967 the electrification and modernisation of the West Coast Main Line (WCML) between Liverpool, Manchester, the West Midlands and London was complete. With the full electrification timetable due to come into operation for the first time on March 6, 1967 everything was set for a new standard in passenger service.

Enjoy more Railway reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

At last something positive would be seen and experienced by both railway passengers and staff after several years of the implementation of the Beeching reshaping.

However, the beginning of the new electrified services was put into serious doubt and overshadowed when, six days before on February 28, 1967, a fatal railway accident occurred on the WCML between Birmingham New Street (BNS) and Coventry.

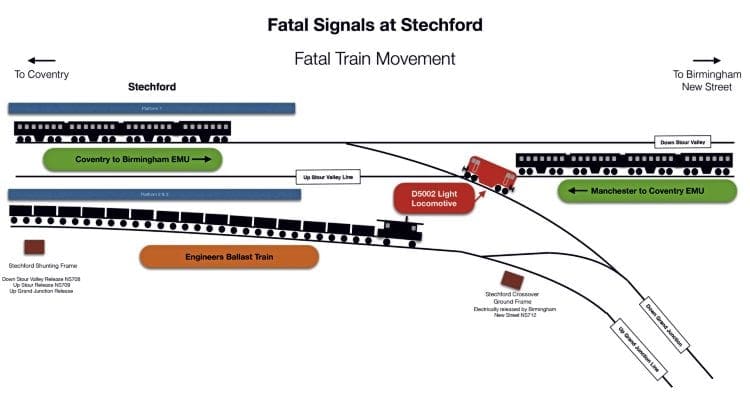

Stechford is situated between Adderley Park and Marston Green and is about 3½ miles from BNS. The main line between Birmingham and Coventry, then known as the Stour Valley Line, was connected via a junction at Stechford to what was known as the Grand Junction line.

Maximum flexibility

The Grand Junction line provides a link between the Birmingham to Coventry main line and the WCML north of Birmingham via Aston and Bescot to/from Stafford and the north, avoiding BNS. The station at Stechford is situated at the junction providing maximum flexibility for the operation of train movements.

As part of the WCML modernisation a significant proportion of signalling was transferred to a series of what were known as ‘power signal boxes’ (PSBs) along the route using electrically powered points and multiple-aspect colour signalling. All lines were track circuited with trains controlled by Track Circuit Block and the standard BR Automatic Warning System (AWS) was also installed.

In February 1967 the PSB at New Street had been open for just over six months and controlled the running lines immediately approaching BNS from all directions, including the Stour Valley line through Stechford and the southerly section of Grand Junction line, together with its junction at Stechford with the Stour Valley line.

Main signalling and points were operated from the new PSB with a number of locally situated ground or shunting frames remaining operational. The operation of the shunting frame at Stechford was dependent on a release by New Street PSB.

In essence, for the new multiple-aspect colour signals to show clear on the Stour Valley line the shunting frame needed to be correctly configured to enable points and signals to be electrically locked by the PSB. The electrical interlocking between points, signals and with relevant shunting frames ensured routes for train services were set up safely and crucially avoided any conflicting movements.

At Stechford there were three point frames;

■ Stechford Shunting Frame (released by New Street PSB – switches 708-710)

■ Stechford Sidings Ground Frame (released by New Street PSB – switch 711)

■ Stechford Crossover Ground Frame (Released by New Street PSB – switch 712)

Of the three, the manned Stechford shunting frame enabled the movement of trains over the Up and Down Stour Valley lines and the Up Grand Junction line. However, no train movements could be made by the shunting frame signalman for the running lines or indeed the two ground frames without the permission of a signalman in New Street PSB.

The operation of the shunting frame or either of the two ground frames was facilitated by the turning of one or more release switches by the signalman at New Street PSB. An indicator at the frame concerned would show if the frame had been released for operation.

Regulation

In addition a further safety protection existed in the form of the sectional appendices. These were, and indeed still are, ‘signed’ by drivers, secondmen, guards and other relevant operational staff, and every railway route has one. By what is known as ‘signing the route’ staff confirm they have read and understood the details of a route.

Not only does this relate to things such as the track, speed limits, locations of crossings and bridges, but it also includes standing instructions of what maybe permitted and what may not be permitted in certain circumstances or at locations along a route.

The sectional appendix set out specifically for Stechford that wrong direction movements, except in an emergency, must only be made where there was a fixed signal provided for such movements. In addition a number of general provisions within the appendix related to wrong direction movements where track circuit block is in operation:

1) The signalman’s authority must be obtained, if necessary by telephone, before any wrong direction movement is made

2) Where giving authority for a wrong direction movement to be made, the signalman must have a clear understanding with the driver as to how far the movement may proceed.

A further general appendix instruction also applied to train movements. This referred to diesel and electric locomotives with driving cabs at each end. The instruction stated that when travelling light, locomotives must normally be driven from the leading cab.

The instruction went on to state: “Where short-distance movements are involved, such as crossing from one line to another, or where undue delay would occur through having to change ends for the reverse movement, it may be driven from the trailing cab.

“When a second man is on the locomotive he must then ride in the leading cab ready to sound the warning horn, to signal to the driver to stop and/or apply the brake in an emergency.”

Instructions in the New Street PSB stated: “A signal with appropriate aspects is provided for every normal movement and no other movement must be made, except in an emergency….”

The modernisation of the line with new track circuit block, AWS, multiple-aspect signalling and regulation seemingly provided a triple layer of safety protection, or did it?

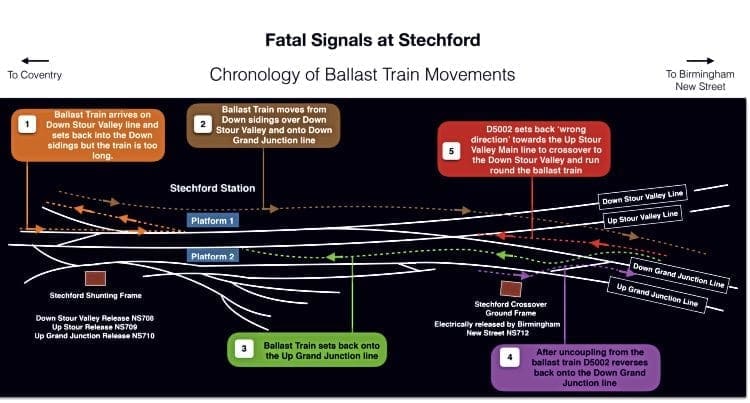

It was Tuesday afternoon on the last day of February 1967 as a ballast train completed its work and approached Stechford on the Down Stour Valley line from the Coventry direction. The train was destined to return to Nuneaton and so would require to be crossed over and reversed at Stechford so as to return to Coventry and then onto Nuneaton.

Years of experience

The ballast train consisted of 26 hopper wagons and three brakevans, one of which was each end of the 787ft- (240m) long train, including the 79¾-ton Class 24 locomotive D5002 (24002). The ballast train’s driver was H D Garrett, based at Nuneaton, and 49 years old. Driver Garratt had 30 years service with the railways, 14 years of which was as a driver.

Garratt was accompanied by secondman B K Sugden, who was 27 years old and had 11 years service in on the railways, seven years of which was as a secondman. The ballast train’s guard was a 36-year-old Coventry man, C R Gooden, who had six years service, mainly as a guard. Signalman C H Curtis came on duty at 14.00 at Stechford shunting frame. Curtis was 64 and nearing retirement.

He had 40 years of experience on the railways and had spent most of his career at one of BNS’s area signalboxes prior to the recent modernisation and introduction of the PSB at New Street.

The head shunter at Stechford on that Tuesday afternoon was R H J Tolster, who had been on duty since 09.00. Tolster was 45 years old and had 11 years service on the railways, all as a shunter at Stechford.

Combined, the staff present at Stechford on that last afternoon of February 1967 had 98 years of railway experience.

Normally, a train that required to return east towards Coventry would be placed in the Down sidings if it needed to clear the Down Stour Valley main line to enable the passage of a through Down service.

If it did not need to do this then it could cross over the Up Stour Valley line and onto the Down Grand Junction line, where it could set back on what was known as No. 1 siding. There was facility at either end of No. 1 siding that enabled a locomotive to be released and run round its train. Trains placed in the Down siding could also make this move and cross over both the Down and Up Stour Valley lines and gain access to the Down Grand Junction line.

As a through service was due through Stechford on the Down Stour Valley line signalman Curtis placed the ballast train in the Down siding. After the through service had passed head shunter Tolster came over to the shunting frame and reported that the ballast train was too long for the locomotive to be run round the train using No. 1 siding.

An exchange then took place between Curtis and Tolster, with the former wanting to carry out the run round moves using crossovers at the Coventry end of the station on the Stour Valley lines; a normal operation for such circumstances.

However, Tolster was insistent that the train should cross over the Down and Up Stour Valley lines to the Down Grand Junction line and set back onto the Up Grand Junction line. Curtis acquiesced to Tolster’s preference.

This meant that Curtis had to contact signalman Bradbury at New Street PSB and ask for the release of the shunting frame and switch 708 to enable the ballast train to make its way over the Stour Valley lines and onto the Down Grand Junction line. Curtis told Bradbury that the train would then be setting back onto the Up Grand Junction line.

Critically, he omitted to tell Bradbury anything further, particularly why the move was being made in this way. Curtis said “that to have told him (Bradbury) would have confused him more than me”. He also failed to mention to Bradbury the need to run the locomotive round the ballast train.

‘Right direction’

Bradbury released switch 708 and the ballast train left the Down siding, crossing and clearing the Down and Up Stour Valley lines and reaching the Down Grand Junction line, passing the crossover with the Up Grand Junction line.

Bradbury at New Street PSB then released switch 712 to enable Tolster, who was in charge of the movement, to set the train back onto the Up Grand Junction line. All these moves had been correct in so far as they had been ‘right direction’.

Tolster then uncoupled the Class 24 locomotive from its train and signalled it to move forward over the crossover to the Down Grand Junction line. As soon as the move was completed he noticed the guard had started walking to the far end (what would become the front of the ballast train) and Tolster wanted him to come back to the rear so he gave the guard a signal with his left hand.

Driver Garratt could not see any of this as he and his second man Sugden had elected to stay in the cab, which was now at the rear (trailing) end of the locomotive. However, Sugden stood at the door of the locomotive to obtain a view of the movements taking place.

Sugden made what was to be a fatal assumption when he saw Tolster give the hand signal. He assumed the hand signal was for him and Garratt to set the locomotive back and onto the Up Stour Valley line.

He told Garratt to proceed and consequently Garratt applied power to the locomotive; a ‘wrong direction’ and unsignalled move had now started.

Critically, because Tolster had sought to attract the guard’s attention immediately after the locomotive had crossed over back to the Down Grand Junction line, he had not replaced lever 1 in the crossover ground frame or contacted New Street PSB to cancel the release on the crossover ground frame.

Further, immediately D5002 had passed back through the crossover Tolster operated the crossover points, normalising them. This defeated the protection that the crossover points when reversed provided to the Stour Valley line.

Second man Sugden had seen Tolster do this, which partly led him to assume the hand signal was for the locomotive to set back. Consequently, what was to be a path to tragedy was clear for D5002 with Garratt and Sugden proceeding towards the Up Main Stour Valley line between Birmingham and Coventry.

The triple protection of the rules, reversed points and effective communication had been thwarted by assumption, sloppy application and apparent indifference. It was to be a short cut to tragedy.

Tolster had not noticed the locomotive making the ‘wrong direction’ move. Effectively, the locomotive approaching from Tolster’s rear passed him by leaving him powerless and unable to do anything to stop the move.

The speed of the locomotive was estimated to be around 10-15 mph when Sugden, still standing in the doorway of the locomotive, noticed an electrical multiple unit arriving from Coventry at the Down platform.

It was at this point he realised something was badly wrong as they were heading for the Down Stour Valley line, which the EMU was occupying in Stechford station. Sugden immediately shouted to Garratt to stop.

Garratt made a full brake application as the locomotive was approaching the crossover with the Up Stour Valley line. The horn of BR AM4 EMU No. 026 (later 304026) was sounded as it approached Stechford at around 50 mph with a Manchester to Coventry service on the Up Stour Valley line.

Unfortunately, and not through any fault of the EMU and its driver, who could do nothing else, the warning was too little and too late. The EMU from Coventry approaching the Down Stour Valley line had not been spotted as early as it could have been if, as the rules required, the driver and second man had been in the leading cab of D5002.

Indeed, the 152-ton EMU approaching Stechford at speed on the Up Stour Valley line, could not be seen at all from the trailing cab of the diesel. Matters were further compounded by the direct air brake system of the Class 24s that required, when operating light, a ‘build up’ time of around 4 seconds.

It was subsequently found that D5002 took 5.8 seconds on one bogie and 7 seconds on the other bogie to build up pressure.

Glancing blow

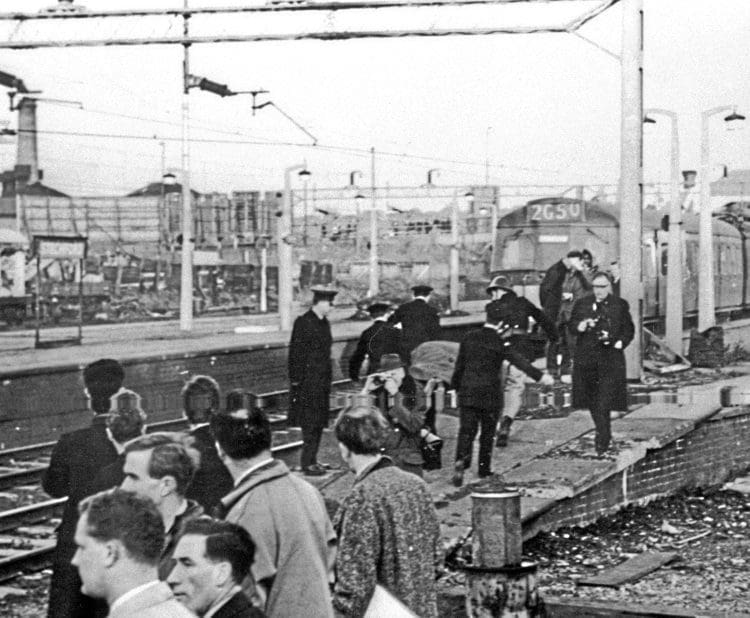

Consequently, the brake application proved unable to arrest D5002 before it had just fouled the Up Stour Valley line as it eventually came to a halt. There was no time nor chance for avoidance of a collision, the EMU hit a glancing blow to the front of No. D5002.

Driver Burton in the Manchester to Coventry EMU was killed instantly. The force caused the four-coach EMU to derail and lurch to the right taking out two electrification stanchions and a colour light signal.

The front two coaches went on their sides sustaining severe damage. Part of the roofs were torn away as the carriages slid on their sides past the stanchions, effectively peeling the roofs off.

It was in these two front coaches that most of the serious injuries were experienced. Eight passengers died as well as the driver, and some 16 people were injured.

The third and fourth carriage remained upright, with the EMU coming to rest some 500ft (168m) beyond D5002, which it had hit a glancing blow, and within 50ft (15m) of the Down platform, where a Coventry-Birmingham EMU stood. The Class 24 was derailed, but not badly damaged.

The emergency services were on the scene within eight minutes with Colonel D McMullen, the inspector who led the inquiry into the accident, praising the performance of the blue light services.

Those that consider themselves scholars of that most infamous of maritime disasters, the sinking of the RMS Titanic, will have come to appreciate that the loss of the vessel and so many souls was not simply caused by the ship hitting an iceberg.

It was a number of elements coming together on that fateful night that led to the ship hitting the iceberg, it foundering and the major loss of life. Stechford 1967 is in many respects a railway equivalent of the 1912 maritime tragedy, albeit, without diminishing the loss of nine lives, it thankfully did not lead to major numbers of fatalities.

The elements of poor or no communication, assumption, over-familiarity, sub-conscious contempt for the rules belied the length of experience of those involved, who should and indeed did know better.

The opportunity for an accident was set from the minute the head shunter, Tolster, insisted the run round would need to be done involving wrong direction moves. Curtis, a signalman with some 40 years experience, knew the risks this would have involved and that it was regarded as prohibited except in an emergency.

The first potential check of the intention was missed when Curtis did not put up enough resistance to the proposal and instead agreed to the planned move. He compounded this and placed more likelihood of a mishap into the mix when he saw fit not to tell Bradbury at New Street PSB the full details of the moves that were planned.

Instructions ignored

Garratt and Sugden haplessly made their contribution to the disaster by ignoring the general appendix instructions regarding travelling in the leading cab of a light locomotive and preferring to remain in what became the trailing cab of the locomotive in the final moments before the accident.

Head shunter Tolster, who Colonel McMullen in his report laid the most responsibility on, set things on course for disaster by using an unclear hand signal, by not reversing the crossover points or replacing lever 1.

He said he had intended to contact the power box immediately he had replaced the crossover points to normal and ask them to give permission to make the wrong direction moves for the ballast train.

The second man Sugden, while standing in the doorway of D5002, assumed a hand signal from Tolster was an indication for the loco to move and set back from the Down Grand Junction over Stour Valley lines. Garratt, as driver, accepted Sugden’s word and made no attempt to check what was an assumption and that would soon lead to fatal consequences.

A final opportunity to avert disaster was missed when D5002 passed Tolster – Sugden could have shouted to him to check the hand signal was for them to set back. He chose not to or did not think to do so.

The poor braking performance of the Class 24 was another component meaning that despite the brakes being fully applied the locomotive failed to stop before it just fouled the Up Stour Valley line.

The failure of the crossover to protect the Stour Valley line was understandable as no one would have considered lever 1 and the points being left clear from a previous move to pose a risk to the Stour Valley running lines, simply because it was against the rules.

It was inconceivable that a train would be set back without a signal and in a ‘wrong direction’ move with the points left clear.

Finally, the breathtaking element that also played a part was the lack of communication, the head shunter making no attempt to speak with driver Garratt and coming to ‘a clear understanding’ as to what moves were to be made as the rules required.

Despite all of this Colonel McMullen praised Tolster for his forthright evidence and the fact that he did not attempt to excuse himself for what he realised were his failures.

Modern signalling was exonerated by the enquiry. Stechford stands as an example of a failure of application by those who knew better, but who on that fateful final day of February 50 years ago all chose to do less than what was expected with fatal consequences for nine people.

Stechford reminds everyone who operate our railways of the need to follow working instructions, communicate and obey all signals conscientiously as a habit and standard that is never negotiable.

83 days later………

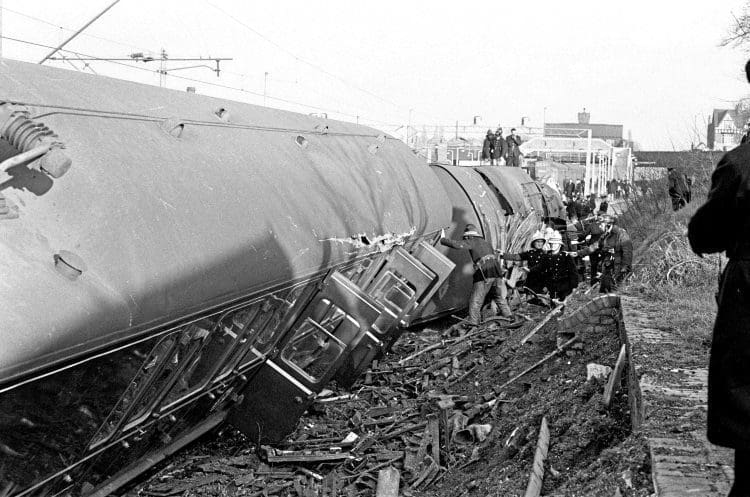

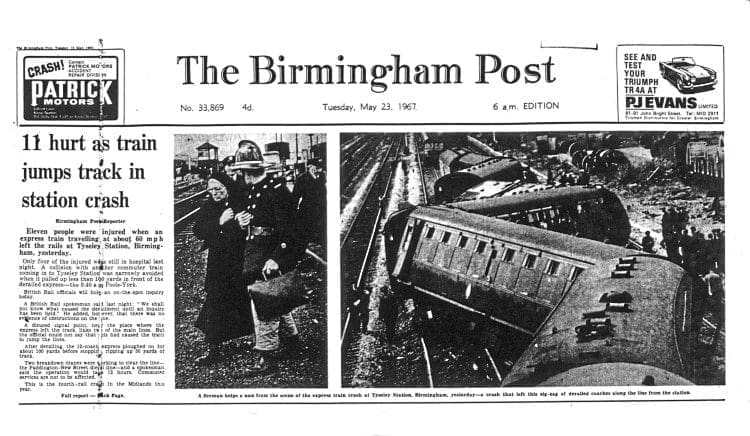

JUST 83 days after the tragic events at Stechford a derailment took place a couple of miles

south-west of Stechford on May 22, 1967.

A Poole to Newcastle express, heading for St Andrews Junction and Birmingham New Street, along the ex-Great Western main line, came off the rails just north of Tyseley station.

The 12-coach express, hauled by Brush Type 4 No. D1714 (later 47 124), was running under clear signals at an estimated speed of 60-65mph on the Down main line. Its driver Mr E J Davies, hearing what he later described as ‘a terrific bang’ and experiencing the locomotive lift upwards, made a full application of the brakes.

A diesel multiple unit, forming a Birmingham Moor Street to Stratford-upon-Avon passenger service, was approaching from the opposite direction as the rear of D1714 derailed, slewing towards and fouling the Up relief line.

The Stratford- bound DMU was approaching on that line and driver C J Dutton, who had been route learning in the cab of D1714, realising the situation, jumped down waving his hands for the DMU to stop.

DMU driver R E Allen had seen the accident from about 100 yards and travelling at 40mph had applied the brakes and stopped. He had spotted driver Dutton waving to him and he acknowledged this with the horn.

The derailment had led to the locomotive and all 12 coaches that formed its train coming off the rails, with one coach ending up on its side. Fortunately, there were no fatalities but 12 people required hospital treatment.

The damage sustained to the railway was severe and led to several days of diverted services and the use of lines through Tyseley locomotive works as a means of diversion.

The cause of the derailment was identified as being a bracket on the Brush Type 4 D1714 that was fitted as part of the AWS system on locomotives that operated on Western Region metals, where the original GWR ramp AWS system was still in use.

The bracket became detached and the heavy AWS equipment cantilevered under the locomotive, scraping over the top of the rails of two diamond crossovers south of Tyseley station.

It then scraped the timber barrow crossing at the south end of the station before finally striking and digging into the south end of the AWS ramp for Small Heath South Down main distant signal. With the remaining bolts holding the equipment fractured, it hit a stretcher bar and facing points locking mechanism forcing the opening of the closed switch rail, resulting in the rear bogie of D1714 derailing, with the remainder of its train following suit.

The train took 300 yards to stop from the points and D1714 went on for a further 70 yards beyond the leading coach.

One of the recommendations arising from the subsequent inquiry by Major P M Olver was that bolts holding WR AWS equipment must be tightened with 758lbs ft of torque rather than the 400lbs ft of torque applied previously.

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 121 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.